| EXHIBITIONS NEWS PRESS ABOUT US CONTACT |

|||||

| REPRESENTED ARTISTS | BERTILLE BAK | GWENAEL BELANGER | DEXTER DYMOKE | ANTTI LAITINEN | |

| MARKO MAETAMM | YUDI NOOR | OLIVER PIETSCH | KIM RUGG | ||

| BETTINA SAMSON | SINTA WERNER | ||||

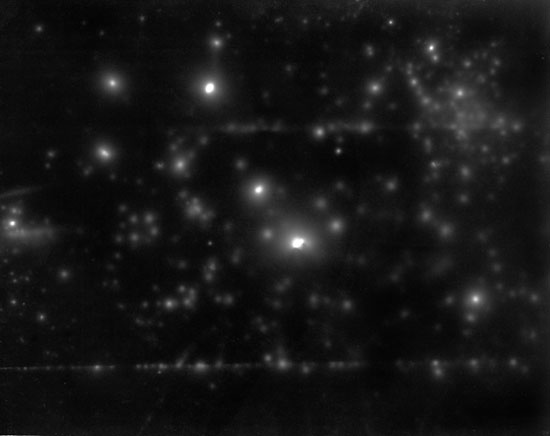

Nuclear Dust #1 and #2 , 2009

Series of two photographic prints

Here a series of big black and white film photographs overlooking an outsized workbench represent the outcome of a home-made scientific experiment: artist Bettina Samson has set out to recreate the chance situation leading Henri Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity in 1896, when he found that uranium left an imprint on photographic plates without the need for any light input. Working in total darkness, Samson exposed sheet film to the radiation of pitchblende, a form of uranium ore, and obtained near-immaterial images which, enlarged, suggest some kind of astronomical phenomenon. Can photos be made without visible light? This process recalls the pioneering use of silver-salts photography as a scientific tool and the way the resultant images were later echoed in abstract painting. Chance and error are both dynamic principles within scientific and artistic research, sharing as they do the same experimental dimension. In the middle of the room there stands, like a monumental tribute to “decisive fortuity”, a stylised marquetry transposition of the scientist’s oak workbench, a near relative of the tradesman’s. Our reading of the work, however, is disturbed by the presence of a translucent yellow plaque with silver letters etched into it, a transcription of the 1939 letter from Albert Einstein to Franklin Roosevelt that triggered the Manhattan Project for an atomic bomb. This ellipsis between two past events highlights the provisional character of our certainties as a factor that renders the notion of scientific progress distinctly problematic.

Text by Pedro Morais in Bettina Samson, Laps & Strats, edition Adera, Lyon, 2009.

© NETTIE HORN